Today’s a sad day.

Not only has Pharrell Williams been speaking at Cannes Lions as if he is a philosopher.

But Ogilvy & Mather’s Twitter account diligently shared it with the part of the world lucky enough not to be there.

To provide some context. Ogily & Mather is the agency that was born out of David Ogilvy’s passion for clear and creative communication.

Ogilvy is heralded as one of the greatest copywriters in the history of copywriting.

His books are part of the staple diet for writers, advertisers, salespeople, business people etc…

Ogily & Mather also employs Rory Sutherland.

Sutherland is a very clever and interesting man.

If you need proof, watch one of his TED talks or read his book.

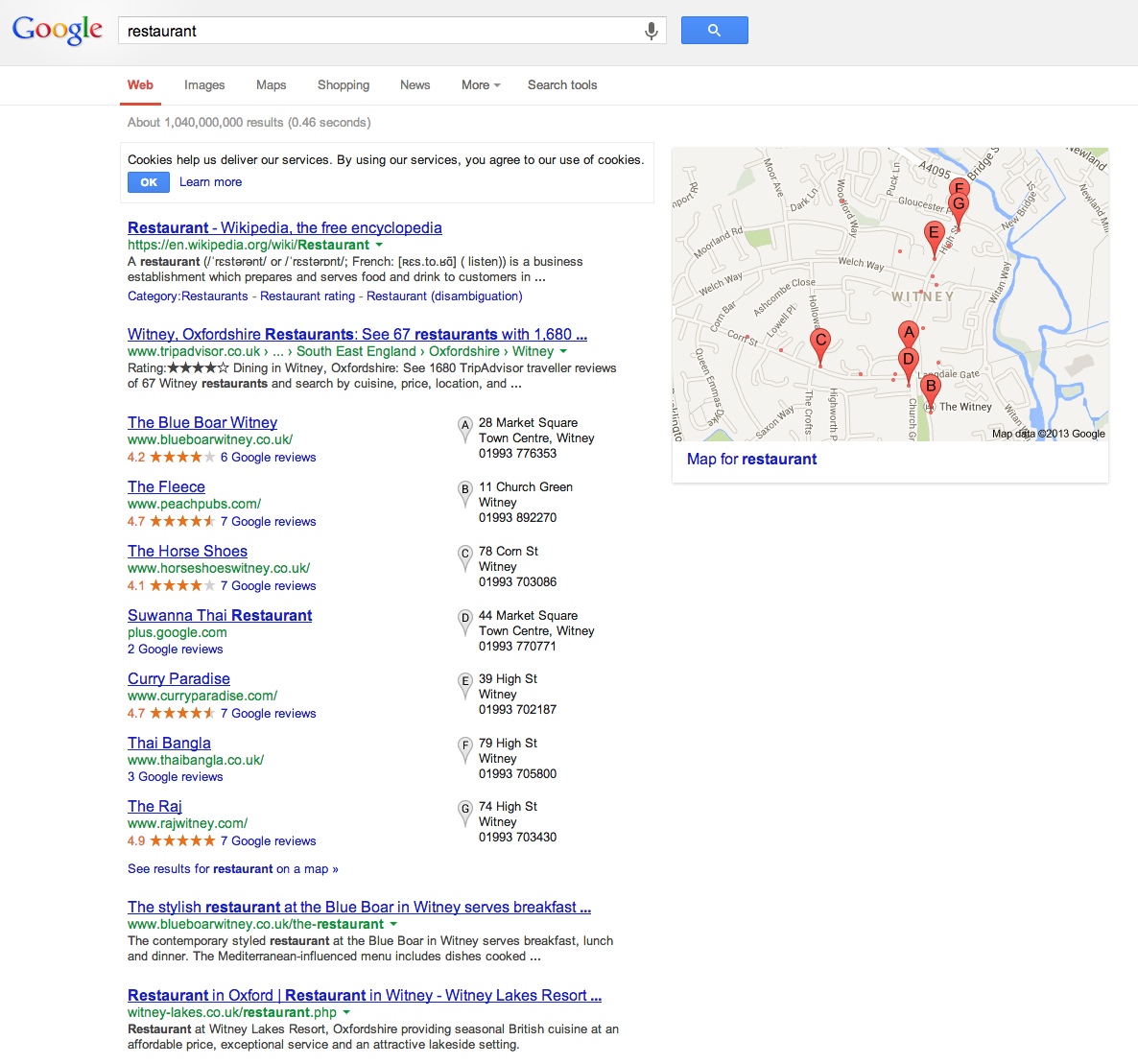

Regardless of all of this pedigree, it doesn’t stop their Twitter account from doing this:

In the tweet, Williams is quoted saying:

Multitasking allows you to keep things different and creative

That sounds lovely.

I love being creative.

And who wants to be the same? Different is so much better.

In that case I’d better get multitasking.

But wait, I’ve just remembered I read a book about this by someone who knows what they are talking about.

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes is a book by Maria Konnikova.

The book is about mindfulness and how, if he were real, Sherlock Holmes would have thought and acted.

Quite early on in the book, Konnikova addresses the theme of multitasking.

Here is a quotation from the book saying such:

We also know, more definitively than we ever have, that our brains are not built for multitasking — something that precludes mindfulness altogether. When we are forced to do multiple things at once, not only do we perform worse on all of them but our memory decreases and our general wellbeing suffers a palpable hit.

To put this back in context, Maria Konnikova is a writer who specialises in psychology.

Pharrell Williams makes pop songs for films with tiny yellow people.

Both are very good at what they do.

But I wouldn’t expect Ogilvy & Mather to tweet about Konnikova’s new song.

It would probably sound like crap.